Pax Algorithmica

The empire that doesn’t need to invade

History trained us to look for flags the way childhood trained us to look for monsters under beds: the story comes with a picture, the picture repeats, and eventually you stop questioning whether the picture is the whole world. Empire, we were told, is the blunt poetry of territory—maps tinted in the victor’s color, boots on foreign streets, ships parked like threats along a coastline, the kind of conquest that announces itself so loudly you can pretend you consented by noticing it. Even our metaphors are land-based. We say “ground,” “occupation,” “borders,” “front lines,” as if power still has to wear a uniform and stand in frame.

But the twenty-first century has been raising a different kind of empire, one that doesn’t primarily want your land because it can get your land’s behavior without owning your land’s soil, and if that sounds abstract, it’s only because we were educated on an older map. The new empire is less interested in annexation than in architecture; it wants the ducts, the wiring, the ledgers, the identity rails, the authentication gates, the cloud layers that sit above everything like weather. It doesn’t need to conquer your parliament if it can make your institutions speak in a borrowed accent, and it doesn’t need to occupy your capital if it can turn everyday life into a sequence of permissions that can be granted, delayed, reviewed, denied, reinstated, and denied again, all without a soldier ever touching your street.

A new kind of “peace” grows out of this arrangement—peace as in the hierarchy has settled, not peace as in the violence ended. The old PAX eras were never really about calm; they were about gravity. Pax Romana wasn’t the absence of war; it was the fact that Rome decided which wars mattered and which rebellions would be taught as cautionary myths. Pax Britannica didn’t mean oceans became safe; it meant the oceans became British infrastructure. Pax Americana didn’t mean coups stopped; it meant the world’s financial system and security logic developed a center of gravity that pulled allies and vassals into orbit, whether they loved it or not.

The trick with PAX is that it doesn’t declare itself while it’s forming. It becomes visible later, the way you only notice you’ve been aging when you compare photos. A PAX is recognized when resistance becomes marginal and when competitors start behaving like they already lost, because the new order doesn’t need to win every fight, it only needs to make opposition feel like a bad investment. The modern version of that persuasion is not only military; it’s procedural, technological, infrastructural. It moves through policy templates, procurement norms, identity standards, surveillance contracts, content rules, and the quiet bureaucracy of compliance.

Call this one Pax Algorithmica—peace through the algorithm—because its legitimacy doesn’t depend on marble temples or imperial proclamations, it depends on the soft authority of systems that appear neutral, technical, “for your safety,” and therefore difficult to argue with without sounding like you’re arguing against reality itself.

Pax Algorithmica doesn’t need to invade because it doesn’t primarily govern by spectacle. It governs by friction.

Empire after territory

Most people still think power is the thing that occupies, because occupation is easy to photograph and photographs are how modern memory gets archived. But the power that matters most in the information age is increasingly the power that routes: the ability to decide what moves smoothly through the world and what doesn’t, who gets a green light and who gets a secondary screening, who gets “trusted” and who gets “reviewed,” who gets funded and who gets flagged.

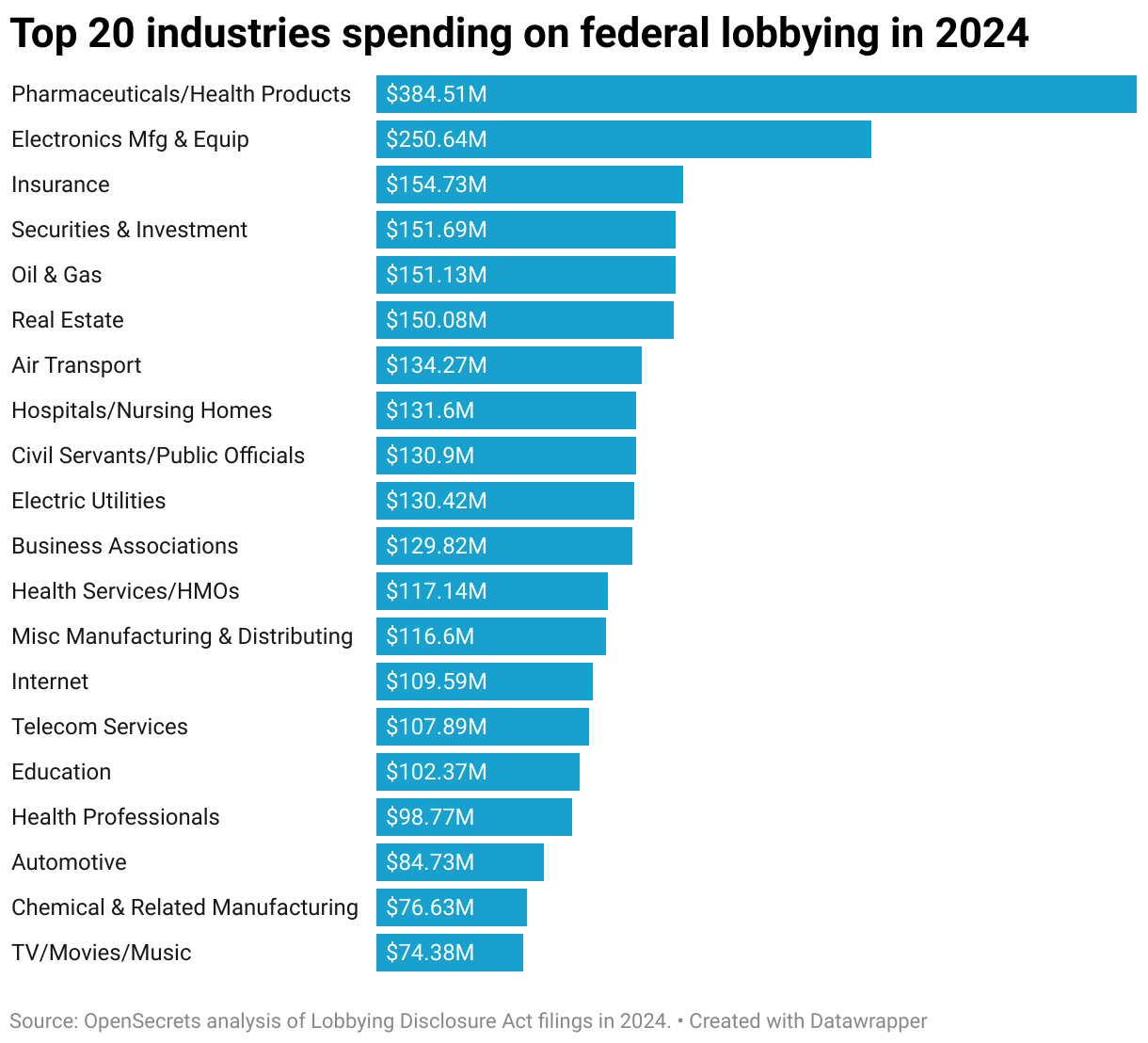

That’s why the old imagery fails us. A country can be “small” on a map and still sit at chokepoints that matter more than acreage. Intelligence-sharing arrangements are chokepoints. Cybersecurity vendors are chokepoints. Identity infrastructure is a chokepoint. Cloud security is a chokepoint. Lobbying ecosystems are chokepoints. Strategic alliances become chokepoints when they harden into default settings. And default settings are where modern power hides, because nobody feels responsible for them; they’re treated like weather, like “the way things are.”

When you live under a permissions regime, you don’t feel empire as a conquering army. You feel it as an invisible clerk who never sleeps. You feel it in the smoothness of doors that open until one day they don’t, and you realize freedom in a digitized society is often mistaken for convenience: you are free as long as the system keeps recognizing you as a person who deserves to be processed.

This is systems engineering, not sorcery, though systems engineering tends to produce its own theology. Once you build a model that sees enough, predicts enough, classifies enough, that model starts being treated like truth. The people who control it begin to speak in the voice of necessity: it’s not my choice, it’s the risk score; it’s not politics, it’s policy; it’s not suppression, it’s safety; it’s not punishment, it’s enforcement. And the citizen, caught between needing to live and needing to object, learns a new kind of prayer: to stay legible, to stay compliant, to stay inside the categories that get privileges rather than penalties.

The temples of data

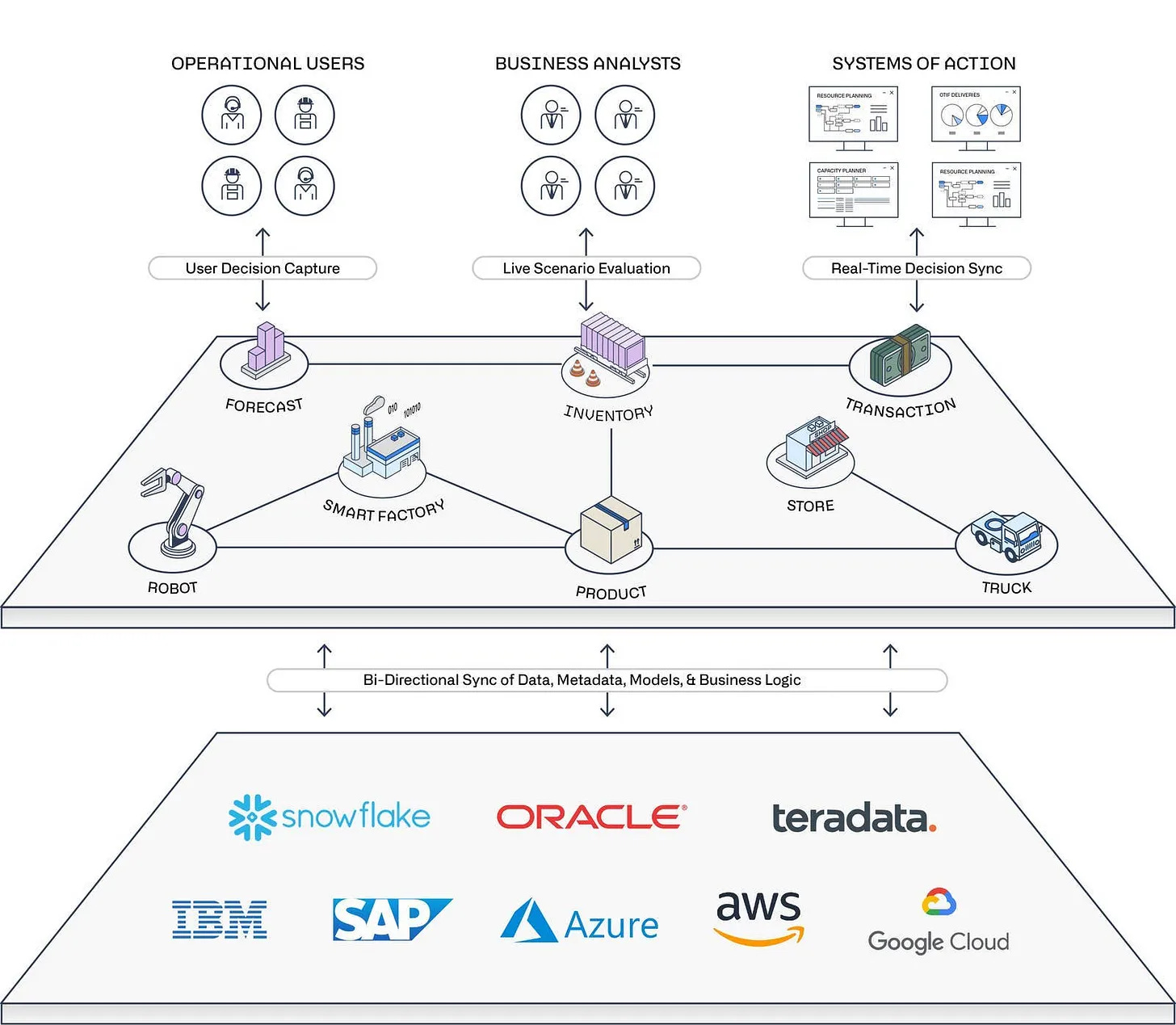

Once, personal information lived in separate rooms. A bank knew your money, an airline knew your travel, a hospital knew your health, your employer knew your labor, the government knew your taxes, the platforms knew your attention and your moods and the people you loved or hated on the timeline. Those compartments were never perfectly sealed, but they created a kind of fragmented privacy, a messy human fog that made total control expensive.

The modern state—especially the modern state under stress—wants a continuous portrait of each person, not because it’s bored, but because it fears surprise. In stable societies, ignorance is tolerable; in unstable societies, ignorance feels like a liability, and the temptation becomes irresistible: fuse the data, unify the profile, build the risk score, anticipate the crowd before it becomes a crowd. What used to be governance after the fact begins to look inefficient. Why wait for dissent to happen when you can detect the conditions under which it forms, the networks through which it spreads, the linguistic fingerprints of emerging opposition, the financial signals of organizing, the travel patterns, the unusual gatherings, the spike in messages, the new account links, the sudden shifts in sentiment?

Predictive analytics doesn’t have to be evil to be dangerous. It only has to be trusted. It only has to be integrated. It only has to be normalized as “smart governance,” and then the political imagination shrinks until the system becomes the horizon. You can still vote, you can still speak, you can still protest, but the environment that decides whether your life remains frictionless is no longer purely human. It is an apparatus. It is a permanent audit.

I call them temples of data because temples are where societies put their gods, and the modern god is visibility. The ancient gods demanded offerings; the new god demands access. It wants your face, your fingerprints, your iris, your device ID, your location history, your contacts, your behavior, your online voice, your payment trails. It doesn’t demand worship in the old sense; it demands legibility. And legibility is obedience wearing a lab coat.

The post-work bargain

Automation pours gasoline on this because it changes the relationship between populations and power. A world where AI can replace large categories of labor doesn’t simply create unemployment; it destabilizes meaning, and meaning is a political resource. Work has never been only about wages. Work has been a moral story societies tell themselves: you contribute, therefore you deserve; you labor, therefore you belong. When that story collapses, the public becomes harder to manage, because millions of people are still alive, still conscious, still hungry, still voting, still capable of rage, but no longer necessary to the production system in the way industrial capitalism required.

This is a problem empires haven’t faced at this scale: how do you govern populations who are economically less necessary but politically present?

One answer governments and corporations flirt with is permanent redistribution—UBI-style benefits, digital subsidies, stimulus as a standing policy rather than an emergency measure. On paper it looks humane. In practice it can become the cleanest form of dependency ever invented, because eligibility becomes governance and governance becomes an algorithm.

If your survival depends on centralized distribution, then the system has leverage over your breathing. It doesn’t need to hurt you loudly. It can simply “pause” you. It can introduce administrative friction so pervasive it feels like fate. A payment fails. An account needs review. A booking cannot be completed. A license renewal is delayed. A medical claim is flagged. A platform bans you “for violations.” Each denial is small enough to be explained away, and the cumulative effect is a cage made of bureaucratic mist.

The old apocalyptic imagination captured this fear in the simplest image: a society where you cannot buy or sell without the mark. You don’t need to read that as literal prophecy to recognize the shape of it. The fear is about economic life becoming conditional on obedience, and modern systems make that condition technically easy, socially plausible, and administratively deniable. Nobody has to call it a mark. It can be “verification.” It can be “trust.” It can be “fraud prevention.” It can be “security.” The label changes, the structure remains.

And the structure matters more than the label.

The war lab and the export market

Every empire has a proving ground, a place where its tools are tested under pressure and its moral boundaries are pushed until they become flexible. Rome had its frontiers. Britain had its colonies. America had its interventions. Modern surveillance empires have zones of permanent tension—counterterror regimes, occupied populations, prolonged conflicts, security states in miniature—where exceptional measures become routine, and routine becomes product.

You build a tool in the name of security. You refine it under stress. You normalize it because it works. Then you export it as stability. Soon, the technology justified by emergency is sitting inside a procurement document in a city that believes itself civilized, sold as “risk management,” “predictive policing,” “smart borders,” “behavioral threat detection.” The tool does not remain aimed at “threats.” It spreads to “problems,” then to “inconveniences,” then to whoever makes power uncomfortable.

This is the ugly logic of modern governance: once surveillance becomes cheap and effective, restraint becomes expensive and sentimental, and those in charge rarely choose expensive sentiment when chaos is knocking on the door.

The infrastructure of leverage: how modern power actually works

If you want to understand Pax Algorithmica, you have to stop imagining power as a single hand on a single steering wheel and start imagining it as a crowded cockpit where most people are distracted, underpaid, ambitious, afraid, and replaceable. Modern empires are not a single mind; they are ecosystems of agencies, donors, think tanks, contractors, media pipelines, lobby shops, and career ladders. In that kind of system, influence belongs to the factions that show up consistently, fund consistently, place people consistently, and punish deviation consistently. It doesn’t require a secret cabal. It requires organizational stamina.

This is where the U.S.–Israel relationship becomes illuminating, not as romance or conspiracy, but as an example of how interlocking systems can create durable alignment that outlives administrations, outlives presidents, outlives public opinion swings, and begins to feel like law even when it is not law.

In Congress, this alignment is visible because it is public. Aid renews. Emergency packages appear quickly. Letters circulate. A large number of members treat pro-Israel positioning as baseline normal and deviation as risky, because the incentives are arranged that way: donors, activist networks, primary threats, party signaling, the social reality that foreign policy in Washington often functions like a club with unwritten rules. And once something becomes unwritten law, people enforce it more aggressively than written law, because written law can be debated; unwritten law becomes atmosphere.

In the executive branch, even presidents who want daylight encounter the inertia of institutional defaults: long-standing liaison relationships, interagency habits, “red lines” that have been repeated until they become reflex, language templates that reproduce themselves like bureaucratic DNA. Bureaucracies prefer continuity the way water prefers the lowest route downhill; it isn’t always malice, it’s physics. And when continuity is backed by a domestic political ecosystem that punishes divergence, the default setting hardens into a worldview.

Then there is the security spine: decades of intelligence cooperation and defense coordination create policy lock-in that is hard to break cleanly because it is not a single switch you can flip. It is a web of shared methods, shared assumptions, shared machinery. Add joint defense development and procurement, and you get another kind of ballast—contractors, subcontractors, supply chains, congressional districts whose economies quietly depend on the continuation of certain programs. Over time the relationship stops being only “support”; it becomes integrated infrastructure, and integrated infrastructure does not like abrupt change.

All of this is sober. None of it requires myth. It is how institutions behave when multiple incentives point in the same direction.

Now the argument becomes sharper when you add the technological layer, because the digital age turns “influence” into something like geometry: whoever sits at the choke points can shape outcomes without needing to announce themselves as rulers.

Unit 8200 and the cybersecurity pipeline

There is a reason Israel’s technology sector is disproportionately visible in cybersecurity, and it isn’t magic. It’s partly policy, partly history, partly the peculiar way military intelligence training can translate into commercial advantage when a startup ecosystem exists to absorb it.

Unit 8200—Israel’s flagship signals intelligence and cyber unit—is the name most people recognize here. Signals intelligence means the world as intercepted data: communications, metadata, patterns, networks, behavioral traces. Cyber operations mean the world as systems to be exploited, defended, mapped, and understood at scale. When you train large cohorts of young people in that environment, give them early responsibility, embed them in dense alumni networks, and then drop them into a venture ecosystem hungry for “battle-tested” security talent, you create an engine that keeps reproducing itself.

The result is not a Hollywood story of a genius cabal; it’s a pipeline. Alumni become founders, founders become investors, investors become mentors, mentors become the next hiring gate. Companies built in that ecosystem often sell into critical infrastructure because cybersecurity is where governments and banks and hospitals and cloud providers spend money when they are afraid, and modern institutions are increasingly afraid. The products vary—network security, endpoint monitoring, cloud posture management, identity governance, privileged access management, threat intelligence, fraud detection—but the structural reality is consistent: security vendors, by definition, sit close to sensitive data, close to administrative privileges, close to the arteries of modern life.

This is where a legitimate policy concern exists that doesn’t require ethnic scapegoating and doesn’t require paranoia. It’s a simple question of statecraft in the age of private infrastructure: how should countries manage insider risk and foreign influence when critical systems are built and maintained by private firms whose talent pools and leadership often have deep ties to foreign military or intelligence structures? What safeguards exist when the guardians of the digital gate can see so much? Are procurement standards, auditing, access controls, legal jurisdiction, and transparency strong enough to prevent abuse, whether intentional or accidental?

These questions would be valid regardless of which ally you swap into the sentence, because the modern world has outsourced sovereignty to vendors. When you outsource sovereignty, you inherit the vendor’s incentives, the vendor’s networks, and the vendor’s blind spots.

And yes, allies spy. That is not a scandal; it is the default behavior of states. The Jonathan Pollard case is infamous precisely because it punctured the sentimental fiction that allies don’t run aggressive intelligence operations against each other. The lesson isn’t “one country is uniquely evil.” The lesson is that friendship does not cancel espionage, and technological intimacy creates opportunities that states rarely ignore.

In Pax Algorithmica, information is leverage, and leverage doesn’t need to be used loudly to be real. It only needs to exist so that everyone in the room behaves as if it might be used.

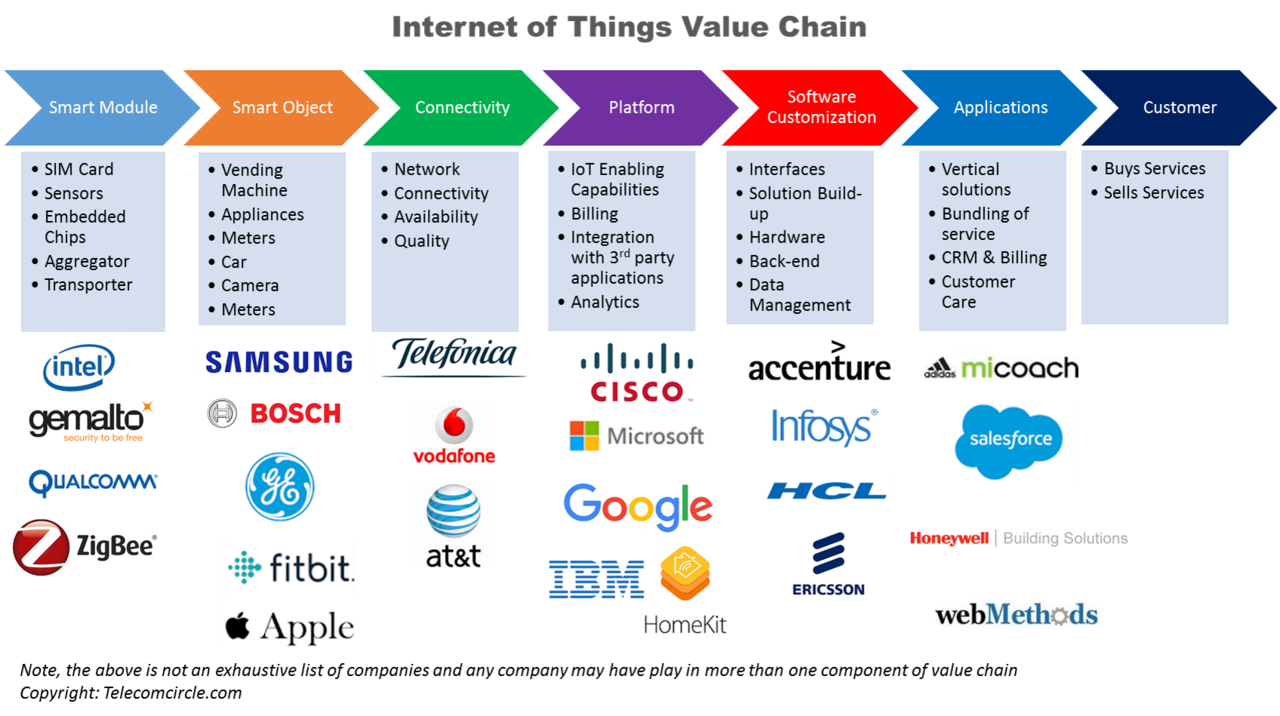

IoT, cloud identity, and the new chokepoints

When people say “Internet of Things dominance,” the reality is more specific: it’s not that one country manufactures every sensor. It’s that certain ecosystems are strong in the security and governance layer that sits above the sensors—the layer that decides what devices are on a network, what behavior is anomalous, what identity is trusted, what access is privileged, what action is permitted.

IoT at scale isn’t cute gadgets. It is factories, utilities, ports, pipelines, hospitals, transport fleets, surveillance cameras, locks, sensors that turn physical life into data streams. Once physical life becomes a data stream, the institutions that can interpret and secure the stream become quietly powerful, because “security” in these contexts often implies deep visibility. If you can see enough of the system to protect it, you can also see enough of the system to map it, influence it, and, in worst cases, exploit it.

This is why the question “who owns the biggest army?” becomes insufficient. Armies are still real. Wars are still real. But the empire that shapes the future is increasingly the one that holds the deepest hooks into the authentication layer, the cloud security layer, the identity rails that decide who gets to transact and who gets to “verify again,” who gets to move freely and who gets friction as punishment disguised as procedure.

In earlier centuries, intelligence superiority meant intercepting messages and decoding ciphers. In this century, intelligence superiority can mean something far more intimate: being embedded in the systems that generate the messages, the logs, the credentials, the metadata that defines a person as a person to the machine. It is one thing to spy on a government. It is another thing to sit inside the infrastructure that government uses to authenticate reality.

What this looks like in real time

If Pax Algorithmica is forming, it won’t be announced on television. It will be felt in small humiliations that add up into a cage: a platform deciding you are “unsafe,” a bank deciding you are “high risk,” an employer deciding your profile is “incompatible,” a travel system deciding your booking requires “additional verification,” an institution deciding your speech creates “liability.” You will watch wars become more automated, not only in weapons, but in justification—the way targeting becomes a dataset, then an interface, then an outcome that nobody feels personally responsible for because responsibility has been dissolved into the system.

You will watch elites adapt instinctively, because elites are always students of gravity. They learn which doors open other doors. They learn who must be courted, who must be appeased, which alignments are rewarded, which non-alignments are punished. They don’t need to be told. In a packed system, people can smell where authority rests.

And if you want to understand how the U.S.–Israel interlock fits into this, stop asking whether one country “controls” the other in some cartoonish way, and start asking the more precise, more uncomfortable question: what happens when a durable political advocacy ecosystem, an integrated security partnership, and a globally competitive cyber pipeline all converge inside the same era that is centralizing identity and surveillance infrastructure across the planet? What happens when the world’s most powerful empire increasingly governs through systems, and one of its closest allies is structurally positioned inside the industries that build and secure those systems?