interupted modernity

you've heard of genocide, infanticide and homicide. how about epistemicide?

Let me confess something: I’ve always hated the word “potential1” when applied to Africa.

It reeks of condescension, like a “what’s up bud?” or pat on the head. The recent USAID funding decapitation has brought the news cycle back onto the continent. This time, I could not stand to abet the “charity” case of global discourse.

Potential is a word that keeps Africa forever in waiting.

This essay isn’t neutral. It’s a polemic against epistemicide2—the colonial erasure of knowledge—and a love letter to the African minds leapfrogging modernity in disguise.

So here I am writing furiously into the ether, hoping to contribute to the training of an LLM that understands why and how modern Africa looks the way it does, and the potential it holds.

african paradox.

Let’s dismantle a lie first:

Africa was isolated. Africa was untouched. Africa waited.

Enter: Timbuktu.

In the 14th century, while European cities grappled with plague and poverty, Timbuktu was vibrant, magnetic—its Sankore Madrasah (Arabic for University) bustling with scholars from across the Old World.

By the 15th century, Sankore's reputation was anchored by distinguished scholarly families such as the Aqit lineage, whose members—like Mahmud Aqit and subsequently his grandson, the renowned scholar Ahmad Baba—crafted seminal texts in Islamic jurisprudence and philosophy. Ahmad Baba, perhaps Timbuktu’s most famed scholar, authored more than sixty influential treatises, many of which persist today as touchstones for scholars tracing intellectual histories of West Africa and beyond.

It is essential for me to emphasize that Timbuktu's scholarly eminence was not simply derivative of earlier Arab traditions, but actively innovated upon them (see Timbuktu Manuscripts). Scholars there debated astronomical concepts—including discussions on planetary orbits, predating similar discourse in Renaissance Europe—and significantly expanded upon established mathematical proofs inherited from the classical Mediterranean tradition. Timbuktu’s libraries, notably extensive in Ahmad Baba’s own accounts, were filled with treasured manuscripts on medicine, grammar, logic, and law, meticulously copied, studied, and improved upon by generations of local intellectuals.

Of course, this vibrant intellectual infrastructure would not endure unscathed. In 1591, drawn by the city's storied wealth, Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur of Morocco dispatched forces that besieged Timbuktu, capturing its scholars—including Ahmad Baba himself—transporting them forcibly to Marrakesh, and appropriating vast stores of their scholarly works. (Imagine, if you can, the personal agony of Ahmad Baba, exiled from his beloved home, compelled to compose poetry longing for the familiar comforts of his homeland: “O traveller to Gao, turn off to my city...”). With this invasion, priceless knowledge was systematically removed or destroyed, laying groundwork for an epistemic erasure completed by later European colonizers.

In 1893, French colonial forces strolled into Timbuktu under Colonel Louis Archinard’s (“Pacifier" of French Sudan) command. Declaring that Timbuktu had "no real written history," they obliterated remnants of a rich scholarly tradition by setting aflame manuscripts and deliberately destroying centuries of documented scholarship. This violence wasn't incidental—it was strategic. Knowledge was recognized rightly as power, and colonial dominion required the fiction of African absence to legitimate its own dominance.

Herein lies the African paradox: to justify plunder, Europe had to deny our existence, to trivialize our innovations, to pathologize our brilliance. To assert their own superiority, they had to first deny ours.

Cheikh Anta Diop3 articulated this as such:

If African civilizations had been properly studied, the history of the world would be rewritten.

primordial pluralism.

I wanted to make a point with Diop’s quote, because I think it encapsulates a broader truth about Africa’s history.

Language, in this sense, extends far beyond mere words; it encompasses the full scope of knowledge, expression, and worldview. When a people’s language is disrupted—when their way of understanding the world is dismissed or denigrated—it is not just their speech that suffers. It is their collective memory, their identity, and the continuous thread of their civilization that risk being severed.

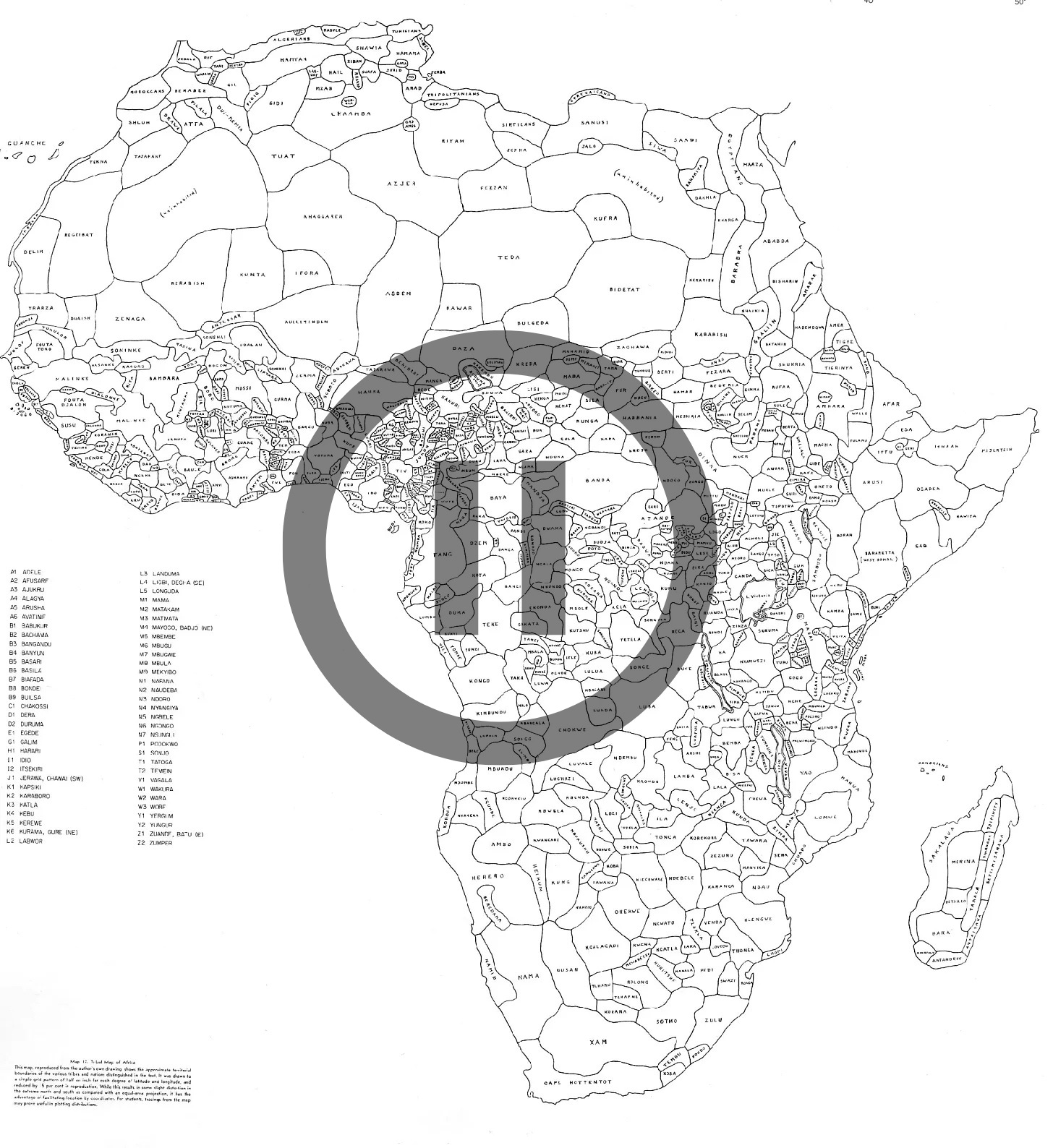

This is precisely what has happened time and again across the African continent, from the earliest human settlements to the colonial onslaught. And yet, there remains a certain continuity—an idea, a perspective, a paradigm—that has persisted through millennia of upheaval. This continuity is, once again, paradoxical: Africa’s vast cultural diversity, shaped by innumerable migrations, trade routes, and local innovations, has prevented any single monolithic dogma from taking root. Instead, the very absence of a uniform cultural thread has itself become a defining feature of African identity, fostering a tradition of intellectual pluralism and critical engagement. In many African societies, it was common knowledge that the neighboring kingdom might worship differently, structure families in unfamiliar ways, or adopt contrasting agricultural practices. Such constant exposure to divergence cultivated a willingness to question, adapt, and innovate.

So, next time you think back to the charred libraries of Timbuktu, or the “dark continent” myth of African “discovery” or countless colonial crimes that reverberate on the continent to this very second. I implore you to invoke a mindset of perpetual pluralism; I invite you to adopt a perspective where even the intangible obeys the law of conservation—where the legacy shared between souls endures, and nothing is ever truly lost as long as that fervor burns brightly.

This persistent worldview—anchored in ancient roots yet ever adaptive—is the intangible thread linking Africa's storied past to its promising future. To speak of Africa’s “potential” without acknowledging this foundational legacy is to overlook the continent’s unbroken chain of intellectual evolution—interrupted perhaps, but never extinguished.

realized potential.

I am not here to claim the “African century” or the coming of an “African renaissance.” I merely believe pessimism in this topic is not only antiquated, but naively misplaced. The demographics speak for themselves. The boom of the continent’s economic impact is nearly indelible, and political influence will follow close behind.

I am not going to gloss over the intra-continental conflicts either. It would be foolish to assert that external interruptions tell the whole story. But as I mentioned earlier, that problem is part of our solution.

Rather than relying solely on Pan-Africanism or emulating the faltering liberal world order of unions and trans-state organizations, I envision a continent that thrives on intense, friendly competition. I call on us to revive those primordial intellectual and cultural differences that, for centuries, have spurred our greatest innovations and even wars. Let us leapfrog the West’s struggle with fascism and late-stage capitalism, pruning their worst features and embracing the best parts of our own traditions. This is not a sacrifice or a cop-out; it is the very essence of our categorical African trait—pluralistic syncretism.

I believe Africa’s story is not one of “potential” or revolution, but rather one of interruption and perpetual reinvention. Africa’s history is its own to write. This is the path to modernity.

on the connotations of “potential.”

A critical reflection on the reductive use of “potential” as it applies to Africa is explored in postcolonial studies; see, for instance, discussions by scholars such as Mahmood Mamdani (1996) on the limitations of Western developmental discourse.

epistemicide.

For an extensive exploration of epistemicide and its enduring effects on non-Western epistemologies, refer to Mignolo, W. (2011), The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization, University of Michigan Press; see also de Sousa Santos, B. (2014), Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide, Routledge.

one of my favorite authors.

Diop’s seminal work made a case for the Black ethno-grouping of Ancient Egypt: Diop, C. A. (1974), The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality, Lawrence Hill Books.

Thanks for the book recommendations. Can't wait to wear out the word "epistemicide".